Kes Woodward exhibit in Anchorage Alaska

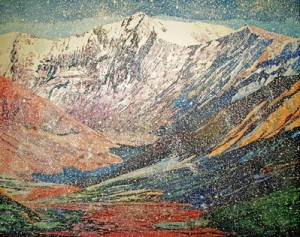

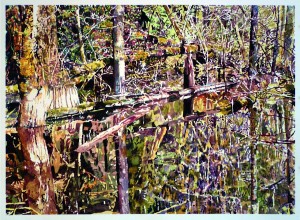

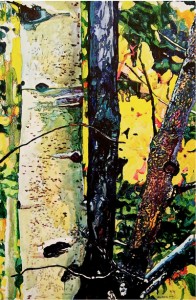

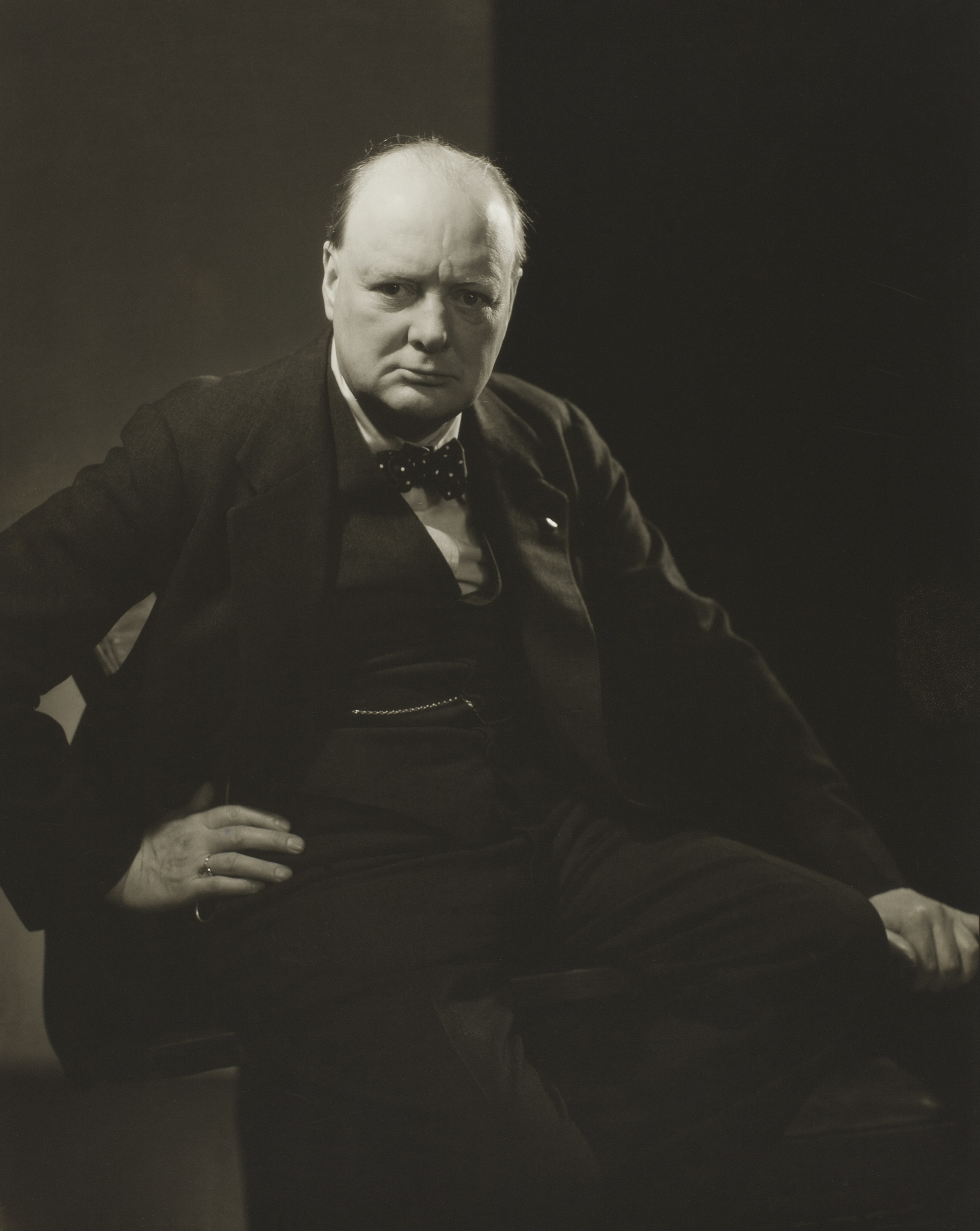

Kesler Woodward, the widely recognized Alaska artist from Fairbanks, will be featured in a solo exhibition at the blue.hollomon gallery. Woodward is best known for his paintings of birch trees and the northern landscape.

This new body of work provides his birch tree “portraits” and his personal view of the Alaska landscape in a range of seasons. In his exhibit catalog last October in Montreal he says, “I made completely abstract, non-representational paintings for years before my images evolved into landscapes.” Woodward also says, “I want my paintings to be very realistic – all about the beauty, wonder, and magic of the thing I’ve painted. But, up close, I want them to be entirely about, color, texture, surface, gesture – all about the paint.”

Woodward has had numerous solo exhibitions spanning his more than 35 years of work in Alaska. He has shown his paintings and has been included in the permanent collections of the Anchorage Museum, the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, the University of Alaska Museum in Fairbanks, and the Morris Museum in Augusta, Georgia among others. His paintings are also included in numerous public, corporate and private collections throughout the United States.

In addition to his active career as an artist, Kesler Woodward has worked in Alaska, first as the Curator of Visual Arts at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, next as the Artistic Director of the Visual Arts Center of Alaska in Anchorage and finally as Professor of Art at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks from 1981 until his retirement in 2000, when he returned to painting on a full-time basis. He is currently a Professor Emeritus of Art at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Woodward has been recognized for his outstanding contributions to the arts by the Alaska State Council on the Arts, the Rasmuson Foundation and the Western States Arts Federation. He is also recognized for his accomplishments as an art historian and curator. He organized three major exhibitions for the Anchorage Museum and wrote four major books on Alaska art for the museum, including Painting in the North, a catalog of the Museum’s permanent collection, and major publications on Alaska artists Sydney Laurence, Eustace Zeigler and Fred Machetanz.

Georgia Blue, co-owner of blue.hollomon gallery with Gina Hollomon, has worked with Woodward since the late 70’s. She says, “Kes is simply the total package. He brings a richness, vitality, intelligence to painting that celebrates the Northern landscape plus his support of other artists is unwavering. He is a treasure!”

“Kes Woodward: New Work”

July 3 – July 26, 2014

Blue.Hollomon Gallery

Anchorage, Alaska

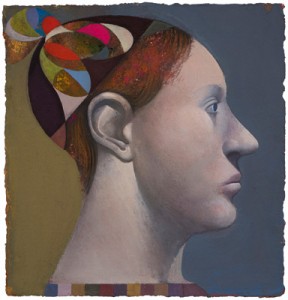

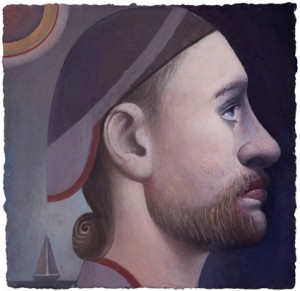

FRAMING SPECIFICATIONS AND ADVICE

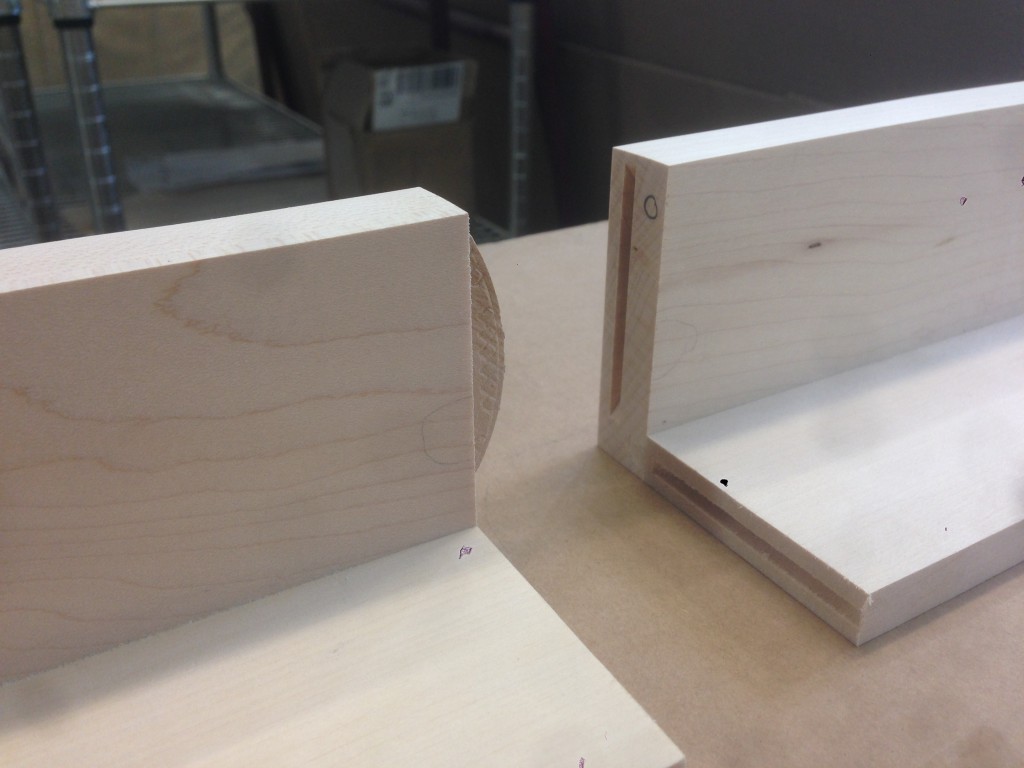

METRO FLOATING FRAME

Deep Floating Profile: 121

Type: floating frame for 1-1/2″ deep canvas paintings

Wood & Finish: ash wood frame with pickled white finish and black interior

Purchasing Option: joined wood frame

Framing Advice: fitting floating frames